“Winter is coming”—a phrase made famous by the sitcom series Game of Thrones—has found an eerie resonance in India. Much like how the people of Winterfell dreaded the arrival of winter and the mythical evil creatures- the White Walkers, in India, it is not a creature, but the polluted air itself, that is dreaded.

Though it’s barely November, a thick layer of pollutants is already blanketing the skies, and all eyes are searching for the culprits. Is it construction waste, crackers, or crop burning? However, one source, which remains largely overlooked, and often slides through the cracks, while continuing to remain the biggest challenge- is vehicular pollution. A recent study by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology confirms this. Conducted in the month of October 2024, the study revealed that stubble burning contributed only 1-2% of Delhi’s total air pollution in the month, while vehicular emissions accounted for a significant 11.2% – 14.2%. This makes vehicle emissions the single biggest identifiable, yet silent contributor to poor air quality, which affects the Indian cities not just in winter but year-round—making it the most urgent problem to address.

Infact, studies being released year after year all indicate how rapidly the situation is deteriorating. The latest report reiterating this, is the Greenpeace report, which spotlights the alarming situation in South Indian cities specifically, which conventionally were believed to have cleaner air. The data from this report suggests the PM2.5 level in these cities is also no better for living standards, with a few like Hyderabad, Chennai, and Visakhapatnam, seeing levels up to 9- 10 times higher than WHO standard. As explained above, a significant part of these rising pollution levels is contributed by the growing population of vehicles.

While the sustainable transport sector has long advocated for walking, cycling, public transport, and clean vehicle technology as solutions, it is clear that combating vehicular pollution requires a multifaceted approach beyond that. This blog outlines three key Mantras (strategies) that cities can adopt right now to tackle this growing menace. Some of these have already been implemented/ in the process of implementation in our lighthouse city, Pimpri Chinchwad, which stands as a good example for many other growing Indian cities.

1. Shift to sustainable modes such as walking, cycling, and public transport

First, cities should focus on creating not just isolated stretches but comprehensive networks of footpaths and cycle tracks. A well-connected network makes sustainable transport options more convenient and accessible, encouraging people to shift to these modes.

However, providing just infrastructure may not be enough in most cases. Cities must invest in raising awareness through campaigns to nudge behavior change. Policies and legislative reforms are also crucial to embedding these practices into the city’s fabric.

What’s a good model to emulate? Many global cities, such as Singapore, have initiated the concept of 15-minute cities. Some Indian Cities have had the chance to adopt this concept, leveraging existing initiatives like the Harit Setu project in Pimpri Chinchwad, which aims to enhance walking and cycling infrastructure in the city. Here, the plan is to make a localised network of connected footpaths and cycling tracks within smaller neighbourhoods, across the city so that people can simply opt to walk or cycle for short distances. Through such interventions, they also get sustainable options for last- mile connectivity.

A glimpse of Linear Garden street, one of the ideal streets in PCMC which prioritises pedestrians and cyclists

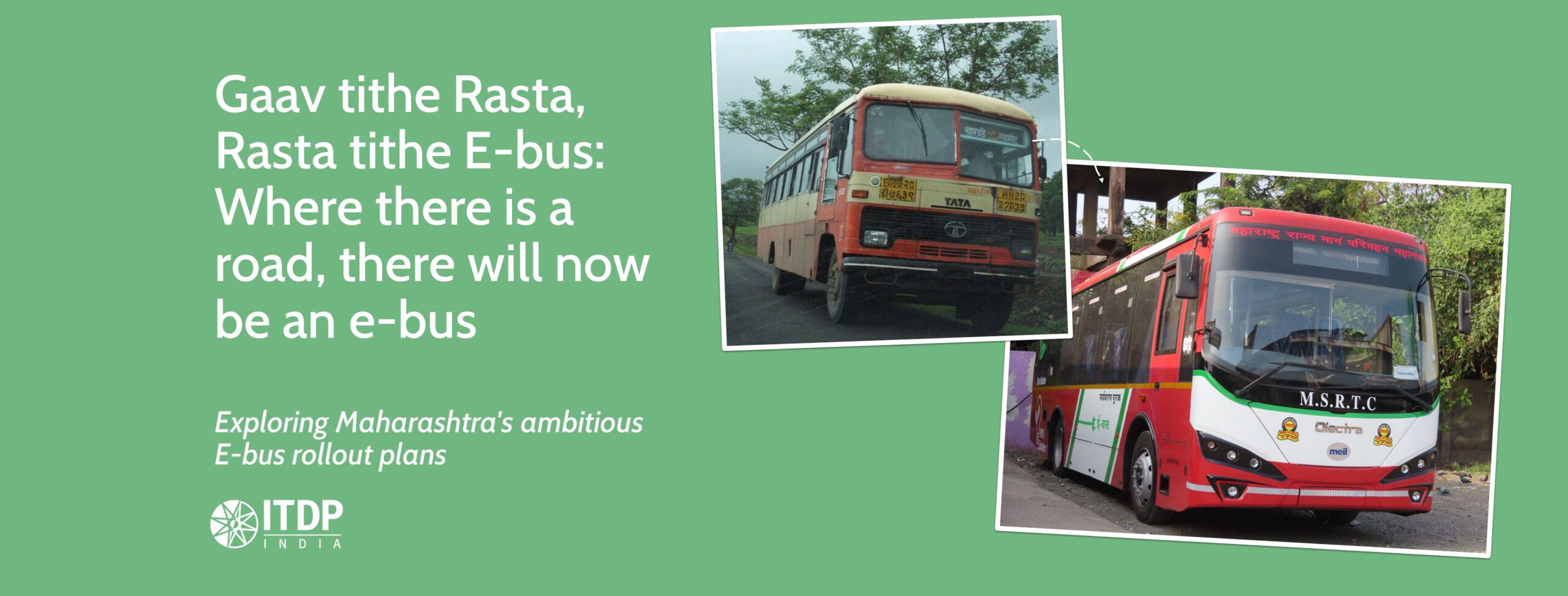

However, while walking and cycling provide a sustainable alternative for short trips, they alone will not reduce congestion or pollution. For longer trips, more and better buses which connect the many networks of roads are the need of the hour to alleviate pollution and congestion. Moreover, improving bus services, including their frequency, reliability, and coverage, is crucial. Buses should seamlessly integrate with other transport modes, such as metro systems, footpaths, and cycle tracks, creating a comprehensive and efficient transport network. This interconnectedness enables commuters to make longer journeys more conveniently, thus making public transport a more attractive option.

While these suggestions might shift a chunk of road users to sustainable modes, there will still be a section who would opt to use personal/private vehicles for travel because of its convenience. To address the emission concerns for that segment, incentivising cleaner vehicles will be an option.

2. Incentivise people to use cleaner vehicles

Alongside promoting sustainable modes of transport, cities need to encourage the use of cleaner vehicles. This can be done in three ways: transitioning to cleaner technologies, scrapping older polluting vehicles, and building robust electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure.

India has already taken a step in this direction by adopting Bharat Stage-VI (BS-VI) emission standards, which significantly reduce emissions from new vehicles. However, cities can push this further by promoting electric vehicles (EVs). Local governments should implement strong scrappage policies that incentivise owners of older, polluting vehicles to retire and scrap them in exchange for financial benefits or rebates on EVs.

Cities also need to upscale their EV infrastructure, particularly by setting up widespread charging stations. A comprehensive EV Readiness Plan can guide cities in developing this infrastructure and ensuring that the transition to EVs is smooth and well-supported.

For example, Pimpri Chinchwad’s Electric Vehicle Readiness Plan 2023 outlines some of these, by setting a goal of having 30% of the new vehicle registrations in city shift to EV by 2026. They are doing so by establishing 100 EV charging stations and offering incentives for e-auto drivers. Property tax rebates are also being offered to those setting up charging point in their properties. Furthermore, the PCMC’s and Pune’s shared bus service, Pune Mahanagar Parivahan Mahamandal Ltd (PMPML), already operates 473 e-buses—India’s third-largest fleet—and is continuing to expand its fleet. These efforts – both on the front improved vehicle technology and on the front of emission reduction through improved public transport, not only reduce emissions but also set the stage for a future where EVs become the primary mode of motorised transport.

Cities infact can go a step further, to effectively promote the use of cleaner vehicles. They can go for a dual approach of simultaneously making it more challenging to rely on personal vehicles.

An electric bus from PMPML fleet

3. Discourage the use of personal vehicles through pricing parking and LEZs

Cities must make it harder for people to rely on private vehicles, especially older, polluting models. Two effective ways to achieve this are by pricing parking and establishing Low Emission Zones (LEZs).

Proper parking management can reduce the number of vehicles on the road by making it expensive to park in public spaces. When parking fees are levied, people think twice before using their cars, potentially avoiding the trip, opting for shorter trips, using public transport or finding other alternative solutions instead. This approach not only discourages unnecessary vehicle use but also frees up critical street space for creating vibrant public spaces on street. When authorised designated spots are demarcated by the city on the streets, it further reduces the time and fuel wasted in searching for a parking spot.

Effective parking management can deter vehicle use, while LEZs take it a step further by restricting the most polluting vehicles from entering key areas. Together, they provide a strong mechanism to reduce vehicular emissions.

In an LEZ, only vehicles with low or zero emissions—such as electric vehicles or those that meet the recommended emission standards (BS-VI)—are allowed to enter. LEZs can be city-wide or focused on strategically selected areas, making them an effective tool for cutting emissions in densely populated regions.

For instance, in cities like London there has been a drastic reduction. As per the Mayor’s report, London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), launched in 2019, has led to a 44% reduction in nitrogen dioxide levels and a roughly 30% decrease in traffic in central areas, alongside a 21% increase in cycling.

In India, a study by ITDP India and ICCT in Pimpri Chinchwad found that restricting pre-BS-VI vehicles in a designated LEZ could reduce PM 2.5 emissions by up to 91% within a year (if all the pre-BS-VI users switch to EVs). Without such measures, pollution levels will decrease by only 50% in the next five years, under current practices (which involves the expected business as usual gradual natural transition to BS-VI).

Designated parking spaces created on a street in PCMC

While these three Mantras provide a holistic approach to combat vehicular emissions, acknowledging the issue is the first step. We urge cities and policymakers not to let air pollution caused by vehicles fade into the background or be treated as a seasonal issue. Addressing vehicular emissions requires year-round effort—mode shift, cleaner vehicle technologies, and Low Emission Zones must work in tandem to tackle pollution from all angles.

Written by Donita Jose, Senior Associate, Communications and Development, ITDP India

With technical inputs from Parin Visariya, Deputy Manager at ITDP India

Consultation with Nashik Municipal Corporation

Consultation with Nashik Municipal Corporation