9 minutes read time

Over the last one year, Nagpur really hit the streets, quite literally. The Nagpur Municipal Corporation, with technical support from ITDP India studied the walkability and cyclability of seven major roads covering 10 km. Over 330+ citizens were also surveyed to find the best-performing, most walkable, and cycle-friendly street in Nagpur city!

And guess what? We found a clear winner.

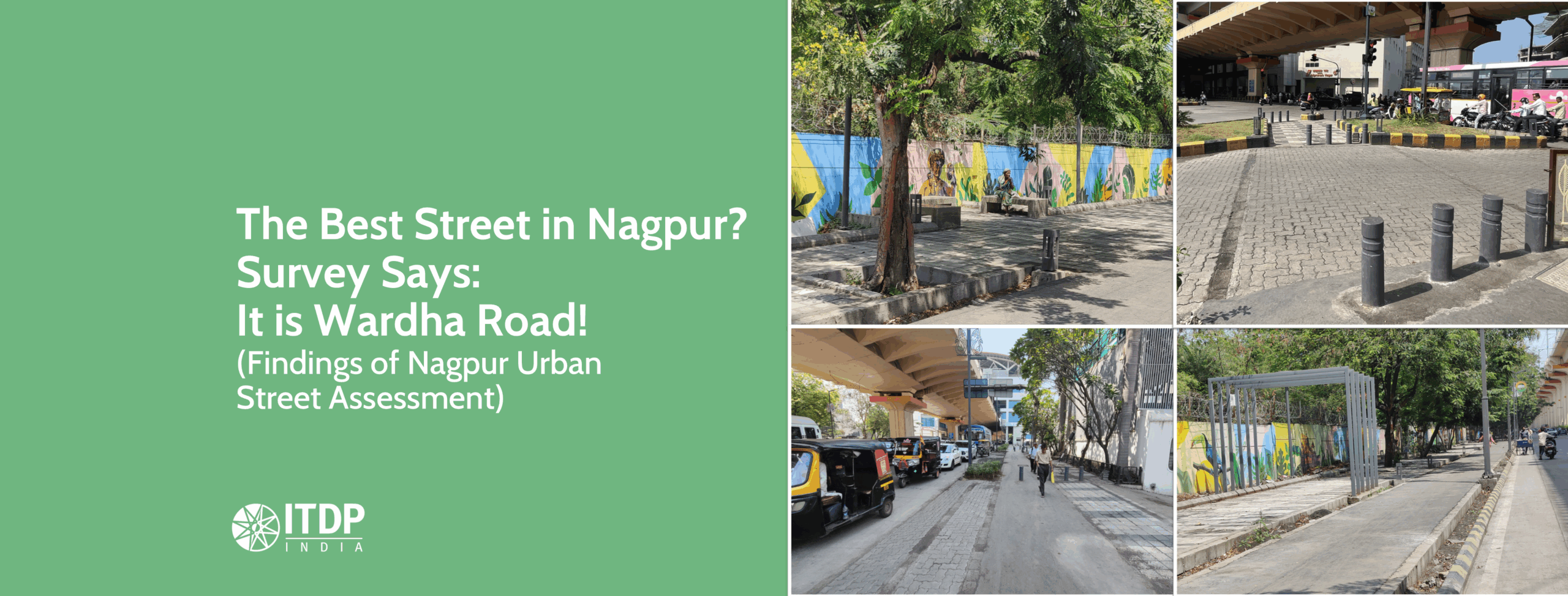

Drumroll for… Wardha Road A, the 1.3 km stretch from Ajni Square to Rahate Colony, was the clear choice of Nagpurians as the most walkable and cycle friendly street!

These were the findings from Nagpur Urban Street Assessment Report, launched in July 2025.

Why is Wardha Road A the best street in Nagpur?

Wardha Road A scored 24.75/30 in a citywide assessment and was found to be the most walkable and cycle-friendly street in Nagpur.

From a first glance itself, it has a mix of all things considered must have in urban design! The survey found that:

- The street on both Left Hand Side (LHS) and Right Hand Side (RHS) had 86% and 88% usable footpaths offering a continuous connectivity for all walking users.

- In terms of cycle track availability, both sides have 92% continuous connectivity of cycle tracks.

- If this wasn’t all, it was observed nearly 100% pedestrians were using the footpath.

- In terms of people’ perception of the street, Wardha Road A performed exceedingly well! 87% of the people felt walkability and cyclability improved on the street. Overall perception of safety while crossing street was also above 80%.

Furthermore, with 55 shaded trees, 11 seats, 35 pedestrian lights, and a generous footpath of 3m wide along with 2m wide cycle tracks, this street had every Nagpurkar raving!

Just next door, but a whole different world

To understand how individual streets have performed, let’s zoom out. Surrounding Wardha Road A are three major streets:

- Wardha Road B

- Ring Road (South/ Southwest)

- Central Bazaar Road (Northwest)

Despite being part of the same road network, their conditions tell a different story.

Here’s how they score:

- Wardha Road A: 24.75

- Wardha Road B: 18.75

- Ring Road: 6.5

- Central Bazaar Road: 6.75

These numbers reflect a sharp drop in quality and accessibility of streets.

For instance:

- Wardha Road B, which is also redesigned alongside the Wardha Road A, scored lower on multiple fronts. In the perception surveys, while Wardha road A scored an 83% from citizens for ease of crossing, Wardha Road B scored 77%. In our observation surveys as well, Wardha road B had a whopping 249 obstructions as compared to its counterpart Wardha Road A which had just 76 obstructions.

- Ring Road which is barely few hundred meters from Wardha Road A also suffered from lowest scores! Our observation study spotted 199 obstructions. This road also lacked a cycle track all together, despite volume counts showing there were a whopping 160 cyclists here per hour, highest among all surveyed streets. This shows that even if a person sets out to cycle from Wardha to Ring Road, with lack of continuous footpaths, their journey will be unsafe.

- To the north of Wardha Road A is another street, Central Bazaar Road. In the survey the stretch from Lokmat Square to Bajajnagar Square was surveyed and we found that 100% of the pedestrians were forced to walk off the footpath, on the carriageway, in contrast with Wardha road A where continuous connectivity was possible.

So, while Wardha Road A may be a star, the surrounding roads are failing to keep up. Moreover, if a citizen were to decide to walk or cycle from Wardha A to Wardha B, their journeys would widely differ, encouraging them to NOT choose these sustainable modes, and instead rely on personal vehicles.

This stark contrast makes one thing clear: safe streets cannot remain isolated stretches. Walking or cycling across even adjacent roads is inconsistent and unsafe, pushing people toward personal vehicle use.

How Did the Study Get These Insights?

The study used a three-part approach: design surveys, observation studies, and perception surveys.

1. Design Surveys- Our teams hit the ground for the analysis of design features of the streets

2. Observation Studies – Next we observed how people moved, walked, and cycled on the infrastructure.

3. Perception Studies – Finally, we reached out to street users to understand their perception about the streets!

Key Takeaways from Nagpur Street Audit:

1. Speeds are high on Nagpur roads

One of the striking findings of the survey was the high speeds observed on vehicles plying the streets. Be it two-wheeler or four-wheeler, the average speeds were far higher than Indian Road Congress standards. For instance, during our survey we used speed guns, and they revealed peak vehicular speeds of over 60 km/h on most roads, with some stretches (Orange City Road and Amravati Road) recording up to 75 km/h for two-wheelers. The ideal speed limit within cities should be around 30-40 kmph. Anything higher than this means that in case of a road crash, likelihood of death is high!

This finding was echoed by citizens in their perception surveys. Fast moving vehicles was the biggest concern across all 7 seven roads when we asked them about road safety!

2. All redesigned streets are not performing well

While it is widely considered that having designers on board to redesign streets is a best practice, the city also needs to put in other checks and balances in place to harmonise the street design across the city. In Nagpur for instance, of the seven streets surveyed, four had been redesigned previously. Of the four, three did not perform great either in design, nor observational or the perception surveys. Amravati Road which was redesigned in 2023 has scored an overall score of 12.25 out of 30.

Breaking down this score we find that when it came to design, only 33% and 38% of the LHS and RHS footpaths were usable. When it came to usability of cycle tracks, just 55% and 65% of footpath had usable tracks.

In our observation surveys we also found that nearly 60% did not walk on footpaths. In terms of people’s perception as well only 45% felt walkability improved and 52% cyclability improved.

3. Streets are not yet safe for vulnerable users of Nagpur

A street safe for kids has low traffic speeds, safe pedestrian crossings, and ample space for walking and play, that is free from hazards and obstructions. Our surveys found that most streets lacked traffic calming features and safe pedestrian crossings, and these two issues also emerged as key issues in perception studies.

With over 65% of respondents voicing safety concerns for children, the findings highlight a clear opportunity for the city to prioritise Safe School Zones and create streets that support safe, independent travel for young pedestrians.

4. Obstructions is a big issue

Our observation studies across the 10kms of roads found a whopping 1958 obstructions! They were primarily of three types — vehicles parked on footpath, commercial space spillover, and vending obstruction. This made it extremely difficult for citizens to move on the streets — both to walk and cycle challenging. Infact, our perception study found that citizens were more troubled with parked vehicles on footpath than any other type of obstruction!

5. Construction should be improved

Across the city, footpath construction quality was poor, both in terms of material chosen and implementation. Poor selection of material and workmanship has resulted in bad walking surface, and acts as a walking inhibitor.

So, How Can Nagpur Improve its Streets?

1. Adopt a Network Planning Approach

Nagpur needs a comprehensive street transformation and not just a few great streets; it needs a well-connected network. To encourage more people to walk or cycle, infrastructure must be continuous and safe from Point A to Point B.

This thought process has numerous benefits.

- This can encourage more and more to shift to non-motorised modes for shorter commutes, without having to rely on personal vehicles.

- Apart from helping citizens who are the ultimate end users, a neighbourhood wide streets network approach helps the municipality to undertake work in a phase-wise manner.

- They can also dedicate annual budgets for streets by working towards a plan, onboard expert design consultants, and monitor and evaluate more effectively.

2. Focus on school zones

Nagpur’s streets have many students on them, accessing their schools on foot and cycle. Infact in some streets, the number of cyclists were going up to 160 cyclists in peak hours, majority of whom are captive users like students. This makes school zoning of utmost priority. In a school zone, not only is the area around the school made slower and safer, but there are various provisions like parking, signages, road markings, street furniture, etc. added to make the experience of students and the guardians who pick them better.

Nagpur’s streets have many students on them, accessing their schools on foot and cycle. Infact in some streets, the number of cyclists were going up to 160 cyclists in peak hours, majority of whom are captive users like students. This makes school zoning of utmost priority. In a school zone, not only is the area around the school made slower and safer, but there are various provisions like parking, signages, road markings, street furniture, etc. added to make the experience of students and the guardians who pick them better.

3. Create Urban Street Design Guidelines

Nagpur’s current approach has been fragmented — a few successful redesigns (like Wardha Road A) sit alongside poorly built streets. To fix this, the city should adopt Urban Street Design Guidelines.

These guidelines will further help to:

- Ensure there is uniformity between multiple implementing agencies like Nagpur Municipal Corporation, Nagpur Improvement Trust, Public Works Department in using standardised and robust materials.

- Make tendering processes simpler and uniform, and bring in better quality control with standardisation of material and rates.

5. Adopt the right policies

Progressive policies can help a city set realistic goals and transform ideas into action. For Nagpur, this could happen by adopting a set of policies like a Nagpur Healthy Streets Policy, for starters. This policy can enshrine what the city wants to achieve in future when it comes to walking and cycling. To bolster this, a parking policy will also help Nagpur to have a clear vision on tackling its issue of haphazard parking, as the current assessment spotlights that parking encroachment is the most common form of footpath encroachment.

Written by Donita Jose, Senior Associate, Communication, with technical inputs from Siddhartha Godbole, Senior Associate, Healthy Streets

Edited by Shreesha Arondekar, Associate, Communications and Development

Pictures by Suraj Bartakke,Senior Surveyor & Admin